The global COVID-19 pandemic has serious consequences for not only physical health but also economic and psychological well-being. Governments around the world have encouraged organizations to allow employees to work from home to prevent the coronavirus spread while maintaining production. Work from home (WFH)—also known as telework, telecommuting, flexible workplace, and remote work—is a type of alternative working arrangement in which employees perform their jobs from home by utilizing information and communication technologies (ICTs) to interact with others and complete work duties (Tavares, 2017). Better work-life balance, reduced commuting time, more flexibility, increased perceived autonomy, lower turnover intention, increased job satisfaction, improved productivity, and lower occupational stress are all benefits of WFH (Bloom et al., 2015; Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Tavares, 2017). On the contrary, it faces difficulties such as multitasking, social isolation, decreased work motivation, increased costs, distraction, and limited communication (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Greer & Payne, 2014; Tavares, 2017).

While working remotely has gained popularity around the world as technology advances (Greer & Payne, 2014), Due to limited technology infrastructure, high-context culture, and a lack of dedicated workspace and tools to complete their job (Mustajab et al., 2020; Suarlan, 2018), and distress associated with the need to adapt and cope with new digital technologies, the concept of WFH itself is still not well-known to most organizations (Gaudioso et al., 2017). Home is where people rest and work is done at the office (Mustajab et al., 2020; Suarlan, 2018). Even though some companies already offered WFH before the government made the emergency rules official, most employees were still used to going to the office (Kaushik & Guleria, 2020).

The current working arrangement has only recently emerged as a result of the pandemic. Employees face increased stressors, including not only exaggerated work-life conflict resulting from school and daycare facility closures (Vaziri et al., 2020), but also job insecurity, financial threats, and health concerns (Wilson et al., 2020). Employees’ mental health may suffer; as a result, resulting in poor job performance (Crosbie & Moore, 2004).

There is a trend toward shifting work-related stress toward home-related issues. WFH research is one of the most important research topics in organizational psychology during the pandemic (Kramer & Kramer, 2020). Exploring employees’ mental well-being is critical because emotional states can predict work performance and effective organizational functioning (Burton et al., 2008; Song et al., 2020). As a result, this research aimed to determine how much employees’ psychological well-being affected their work performance during the pandemic. This article assesses the workers’ psychological well-being by measuring their levels of depression, anxiety, and stress, as well as their job performance (Sutarto et al., 2021).

Employees’ Mental Health During the Pandemic

Employees’ mental well-being is an important determinant of overall health and significantly impacts the quality of life and productivity (Burton et al., 2008). Psychological distress, which refers to a state of emotional suffering accompanied by mild to severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and somatic symptoms, has been widely used as an indicator of mental well-being (Drapeau et al., 2012). The unprecedented crisis is a significant source of stressors that worsen employees’ emotional distress (Hamouche, 2020). While most mental health research has focused on high-risk occupational groups like health professionals (Shaukat et al., 2020; Soto-Rubio et al., 2020), few studies have been conducted among those transitioning into WFH. The existing literature suggests that WFH has beneficial effects on psychological health (Bloom et al., 2015; Tavares, 2017).

However, WFH’s mandatory and abrupt implementation results in a lack of evidence and consistency. In one study, Song et al. (2020) discovered that Chinese teleworkers experienced less stress than office workers after resuming work during the pandemic. Purwanto et al. (2020) discovered that Indonesian teachers were less stressed because they had more free time.

Employee productivity and work from home during the pandemic

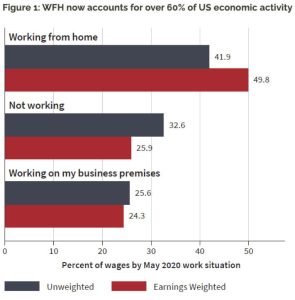

Countries’ ability to WFH during the pandemic varies. Around 40% of jobs could potentially be performed from home in the United States (Dingel & Neiman, 2020) and European countries (Barrot et al., 2021), but only 29.6%–31.2% in developing countries. Globally, approximately 16.67% of all occupations can be performed remotely (ILO, 2020). Despite its potential for widespread use, its effects on productivity during the COVID-19 crisis were inconclusive. A survey of Japanese employees revealed decreased worker productivity (Morikawa, 2020), while another survey in the United States revealed a slight decrease in productivity (Afshar, 2020). Some qualitative studies on Indonesian people found that WFH during the pandemic was more stressful than employees expected, resulting in lower productivity (Mustajab et al., 2020). Other studies, on the other hand, found that Indonesian employees reported higher levels of job satisfaction and motivation, which improved job performance during telework (Susilo, 2020). In other countries, Danish employees reported doing more work than on-site employees; a similar result was found in a survey of US hiring managers (Ozimek, 2020).

During the pandemic, socio-demography, mental health, and productivity were all affected

Few studies have looked at the impact of current, enforced WFH on psychological distress as well as productivity-related outcomes. Moretti et al. (2020) discovered that 51 Italian mobile workers reported less stress and equal satisfaction when compared to working from an office but were less productive. Based on interviews with 24 Indian managers, Jaiswal and Arun (2020) discovered that these managers had increased working hours, lower productivity, and a higher stress level. However, no studies with a larger sample size have been conducted in more general WFH occupations.

This study was founded on Donald et al. (2005) ’s three-factor model of the relationship between stress and productivity, which is generalizable across different employee groups. Individual work stressors, stress outcomes (physical and psychological well-being), and employee productivity are all factored into the model. Only the direct effect of psychological distress on self-rated work performance was highlighted in our proposed model. Furthermore, when investigating factors associated with mental well-being and productivity in WFH, we identified several potential socio-demographic characteristics that served as protective or risk factors: age, gender, marital status, number of children, education level, job experience, job insecurity, and availability of workspace (Neirotti et al., 2019; Qiu et al., 2020; Song et al., 2020; Xiang et al., 2020).

In terms of gender, women generally experience more distress during the pandemic (Jahanshahi et al., 2020; Megatsari et al., 2020; Qiu et al., 2020). Women in Indonesian culture are socialized to prioritize family over work and be the primary caregivers for household chores (Mustajab et al., 2020; Suarlan, 2017), which limits their effective working abilities. Although they were not at high risk of contracting the disease, younger people reported higher levels of distress (Song et al., 2020). Due to the potential increase in the work-life conflict caused by school and daycare closures, marriage and the number of children should be considered as factors. Married people have better psychological health and more life satisfaction than single people (Caputo & Simon, 2013; Grover & Helliwell, 2019), and parenthood is associated with better subjective well-being (Radó, 2020). Nonetheless, we do not know whether marriage and parenthood become protective or risk factors for mental health and job performance as a result of the pandemic’s abrupt shift in daily lives.

Education level may also act as a protective or risk factor for psychological health. For example, nationwide surveys in China and Brazil found that people with higher education reported more distress during the pandemic, whereas recent Indonesian surveys found the opposite (Megatsari et al., 2020). According to the findings, the length of employment had either direct or indirect effects on job performance (Kuo & Ho, 2010). People with more experience have more opportunities to learn new things and improve their skills, leading to a higher productivity level (Schmidt et al., 1986). Concerning job security, the nature of the organization (state/public institution, private enterprise, social organization, or other) must also be considered. Indonesia’s public sector employees are expected to have more job security because their work environment provides associated benefits and more secure welfare. The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted the private enterprise sector, resulting in increased job insecurity for employees (Enrico, 2020). Furthermore, the availability of a dedicated workspace may be a risk factor. It is anchored to physical boundaries, which limit employee productivity due to interruptions in domestic activities (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007).

Regardless of the current WFH as a response to the pandemic, its positive effects on employee productivity provide preliminary evidence that the number of workers willing or able to WFH may be greater than previously estimated. Prior to the pandemic, 7.9% of the global workforce, or approximately 260 million workers from 118 countries, accounting for 86% of global employment) worked from home on a permanent basis (ILO, 2020). WFH has a potential of close to 16% of employees in middle-income countries such as Indonesia. According to a recent survey, most respondents preferred working remotely more frequently in the future, with more than half of on-site workers willing to begin working remotely (Slackhq, 2020). As a result, organizations may decide to make WFH a permanent part of their future working arrangements. They must identify the individual or occupational characteristics that influence employee productivity (Kramer & Kramer, 2020). According to Gottlieb et al. (2020), more than 70% of managerial and professional jobs could be done from home, as could 39.6% of technician and associate professional jobs and 49.6% of clerical support workers. Low- and medium-skilled workers, such as manufacturing operators and workers in elementary occupations, had the lowest ability to work remotely. Individual characteristics such as high-paying occupations, educational attainment, age, and personality all influence WFH feasibility (Raisiene et al., 2020).

Although no differences in productivity were observed across socio-demographic factors, differences in psychological distress were observed, which was also confirmed by our model that psychological health was a strong predictor of employee performance. As a result, organizations must consider these factors when developing strategies to mitigate psychological risks and maintain productivity during WFH, which is consistent with the findings of Raisiene et al. (2020), who discovered that telework efficiency and qualities are affected by gender, age, education, and work experience.

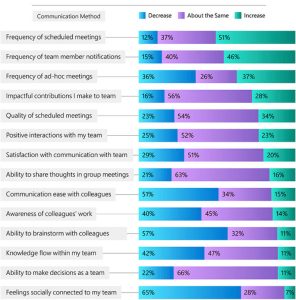

Males were more likely to report work-home interferences and ineffective communication, older generations struggled with self-organization and motivation, and those with less education demonstrated lower organizational commitment. Researchers have identified key challenges for remote workers in the context of the pandemic, such as work-home interference, ineffective communication, and loneliness (Charoensukmongkol & Phungsoonthorn, 2020). Given that such challenges will have an impact on employees’ well-being and productivity during the crisis and beyond, scholars recommend the following strategies: improving communication with coworkers and supervisors, designing flexible work arrangements based on work design perspectives, providing an appropriate working environment (e.g., ICT equipment, a home office, and childcare), and encouraging the sharing of managerial best practices (OECD, 2020). Individuals should consider investing in the infrastructure needed to support WFH and creating home office spaces that discourage interruptions from family members while the pandemic is still ongoing (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007).

Final Thoughts

The coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic has altered the working conditions of millions of employees, who are now based at home and may continue to do so in some capacity for the foreseeable future. Compared to working from an office, the concept of WFH provides greater flexibility and work-life balance. Socio-demographic characteristics, which include gender, age, education level, job experiences, marital status, number of children, and the nature of the organization, all played an important role in the employees’ psychological health but not productivity. The availability of a dedicated workspace influenced both psychological and performance outcomes.

Works Cited

Afshar, V. (2020). Working from home: average productivity loss of remote work is 1%. Retrieved 30 December from:https://www.zdnet.com/article/the-average-productivity-loss-of-remote-work-is-1/

Barrot, J. N., Grassi, B., & Sauvagnat, J. (2021, May). Sectoral effects of social distancing. In AEA Papers and Proceedings (Vol. 111, pp. 277-81).

Bloom, N., Liang, J., Roberts, J., & Ying, Z. J. (2015). Does working from home work? Evidence from a Chinese experiment. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(1), 165-218.

Burton, W. N., Schultz, A. B., Chen, C. Y., & Edington, D. W. (2008). The association of worker productivity and mental health: a review of the literature. International Journal of Workplace Health Management, 1(2),78-94.

Caputo, J., & Simon, R. W. (2013). Physical limitation and emotional well-being: Gender and marital status variations. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(2), 241-257.

Charoensukmongkol, P., & Phungsoonthorn, T. (2021). The effectiveness of supervisor support in lessening perceived uncertainties and emotional exhaustion of university employees during the COVID-19 crisis: the constraining role of organizational intransigence. The Journal of general psychology, 148(4), 431-450.

Crosbie, T., & Moore, J. (2004). Work–life balance and working from home. Social Policy and Society, 3(3), 223-233.

Dingel, J.I. and Neiman, B. (2020). How Many Jobs can be Done at Home?. Working paper, Becker Friedman Institute. Chicago, 19 June 2020.

Donald, I., Taylor, P., Johnson, S., Cooper, C., Cartwright, S. and Robertson, S. (2005). Work environments, stress, and productivity: an examination using ASSET”, International Journal of Stress Management, 12(4),409-423.

Drapeau, A., Marchand, A., & Beaulieu-Prévost, D. (2012). Epidemiology of psychological distress. Mental illnesses-understanding, prediction and control, 69(2), 105-106.

Enrico, B. (2020).Impact of covid-19 upon employment sector in Indonesia. Retrieved 30 December 2022 from: https://iclg.com/briefing/13306-impact-of-covid-19-upon-employment-sector-in-indonesia

Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of applied psychology, 92(6), 1524-1541.

Greer, T. W., & Payne, S. C. (2014). Overcoming telework challenges: Outcomes of successful telework strategies. The Psychologist-Manager Journal, 17(2), 87-111.

Grover, S., & Helliwell, J. F. (2019). How’s life at home? New evidence on marriage and the set point for happiness. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(2), 373-390.

Hamouche, S. (2020). COVID-19 and employees’ mental health: stressors, moderators and agenda for organizational actions. Emerald Open Research, 2, 15.

ILO (2020).Working from home: estimating the worldwide potential. Retrieved 30 December from, https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—ed_protect/—protrav/—travail/documents/briefingnote/wcms_743447.pdf

Jahanshahi, A. A., Dinani, M. M., Madavani, A. N., Li, J., & Zhang, S. X. (2020). The distress of Iranian adults during the Covid-19 pandemic–More distressed than the Chinese and with different predictors. Brain, behavior, and immunity, 87, 124-125.

Jaiswal, A., & Arun, C. J. (2020). Unlocking the COVID-19 lockdown: work from home and its impact on employees.

Kaushik, M., & Guleria, N. (2020). The impact of pandemic COVID-19 in workplace. European Journal of Business and Management, 12(15), 1-10.

Kramer, A., & Kramer, K. Z. (2020). The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, 103442.

Kuo, T. H., & Ho, L. A. (2010). Individual difference and job performance: The relationships among personal factors, job characteristics, flow experience, and service quality. Social Behavior and Personality: an international journal, 38(4), 531-552.

Megatsari, H., Laksono, A. D., Ibad, M., Herwanto, Y. T., Sarweni, K. P., Geno, R. A. P., & Nugraheni, E. (2020). The community psychosocial burden during the COVID-19 pandemic in Indonesia. Heliyon, 6(10), e05136.

Moretti, A., Menna, F., Aulicino, M., Paoletta, M., Liguori, S., & Iolascon, G. (2020). Characterization of home working population during COVID-19 emergency: a cross-sectional analysis. International Journal of environmental research and public health, 17(17), 6284.

Morikawa, M. (2020).COVID-19, teleworking, and productivity. Retrieved 30 December from: https://voxeu.org/article/covid-19-teleworking-and-productivity

Mustajab, D., Bauw, A., Rasyid, A., Irawan, A., Akbar, M. A., & Hamid, M. A. (2020). Working from home phenomenon as an effort to prevent COVID-19 attacks and its impacts on work productivity. TIJAB (The International Journal of Applied Business), 4(1), 13-21.

Neirotti, P., Raguseo, E., & Gastaldi, L. (2019). Designing flexible work practices for job satisfaction: the relation between job characteristics and work disaggregation in different types of work arrangements. New technology, work and employment, 34(2), 116-138.

Ozimek, A. (2020). The future of remote work | press, news & media coverage. Retrieved 30 December from: https://www.upwork.com/press/economics/the-future-of-remote-work/

Qiu, J., Shen, B., Zhao, M., Wang, Z., Xie, B., & Xu, Y. (2020). A nationwide survey of psychological distress among Chinese people in the COVID-19 epidemic: implications and policy recommendations. General psychiatry, 33(2), 10-6.

Radó, M. K. (2020). Tracking the effects of parenthood on subjective well-being: Evidence from Hungary. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(6), 2069-2094.

Raisiene, A. G., Rapuano, V., Varkuleviciute, K., & Stachova, K. (2020). Working from home-Who is happy? A survey of Lithuania’s employees during the COVID-19 quarantine period. Sustainability, 12(13).

Shaukat, N., Ali, D. M., & Razzak, J. (2020). Physical and mental health impacts of COVID-19 on healthcare workers: a scoping review. International Journal of emergency medicine, 13(1), 1-8.

Slackhq (2020), “Report: remote work in the age of covid-19”, Retrieved 30 December 2022, from:https://slackhq.com/report-remote-work-during-coronavirus

Song, L., Wang, Y., Li, Z., Yang, Y., & Li, H. (2020). Mental health and work attitudes among people resuming work during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional study in China. International Journal of environmental research and public health, 17(14), 5059.

Soto-Rubio, A., Giménez-Espert, M. D. C., & Prado-Gascó, V. (2020). Effect of emotional intelligence and psychosocial risks on burnout, job satisfaction, and nurses’ health during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of environmental research and public health, 17(21), 7998.

Suarlan, S. (2018). Teleworking for Indonesian civil servants: Problems and actors. BISNIS & BIROKRASI: Jurnal Ilmu Administrasi dan Organisasi, 24(2), 100-109.

Susilo, D. (2020). Revealing the effect of work-from-home on job performance during the COVID-19 crisis: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business and Government, 26(1), 23-40.

Sutarto, A. P., Wardaningsih, S., & Putri, W. H. (2021). Work from home: Indonesian employees’ mental well-being and productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Workplace Health Management.

Tavares, A. I. (2017). Telework and health effects review. International Journal of Healthcare, 3(2), 30-36.

Vaziri, H., Casper, W. J., Wayne, J. H., & Matthews, R. A. (2020). Changes to the work–family interface during the COVID-19 pandemic: Examining predictors and implications using latent transition analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(10), 1073-1087.

Wilson, J. M., Lee, J., Fitzgerald, H. N., Oosterhoff, B., Sevi, B., & Shook, N. J. (2020). Job insecurity and financial concern during the COVID-19 pandemic are associated with worse mental health. Journal of occupational and environmental medicine, 62(9), 686-691.

Xiang, Y. T., Yang, Y., Li, W., Zhang, L., Zhang, Q., Cheung, T., & Ng, C. H. (2020). Timely mental health care for the 2019 novel coronavirus outbreak is urgently needed. The lancet psychiatry, 7(3), 228-229.

Discussion about this post